Composition no. 92

“What becomes a sign depends on the level of our sensitivity” - Lajos Szabó

.jpg)

Composition no. 92 #1 (Marcel Schwittlick), P1680-B, Artificiata II by Manfred Mohr, Hachure (Matt

DesLauriers), First (0xDEAFBEEF),83 seeds from a vanishing mountain (Sofia Crespo x Anna Ridler) on

display at Paris Photo 2023 (In

Conversation With, presented by NGUYEN WAHED)

Marcel Schwittlick has been exploring how algorithms can be employed in artistic work. Often going from digital to analog and back again, in restless feedback loops, he is now experimenting with the technique of plotter-luminograms, a cameraless photography technique. In his luminograms, the photographs are made by the paper’s exposure to a laser light navigated by an algorithmically-controlled plotter in a darkroom setting. After the laser-light’s choreography is recorded by the light-sensitive silver halide emulsion, the photo paper is developed normally by the artist, just like regular analog photographs.

.jpg)

Composition no. 92

50,8x61cm / 20x24in

FOMA Fomabrom Variant 111 Baryta paper (Natural Gloss / Neutral tone) (255g Triple weight)

.jpg)

Composition no. 92

50,8x61cm / 20x24in

Adox FP Variotone Baryta paper (Matte / Warm Tone) (255g Triple weight)

The series is a playful yet systematic exploration of the potentials of generative art and concrete photography. The main characteristic of concrete art is that it is non-figurative, anti-anecdotal and it is premised on aesthetic autonomy, signifying nothing other than itself. It is an art form that wants to free perception from any a prioris, aiming at opening up new possibilities for rational categories of aesthetic apprehension – an approach that invites us to practice our abilities to decode, differentiate and recognize form and classes of meaning. It brings new perspectives on forms, form relationships and visual orders into consciousness.

.jpg)

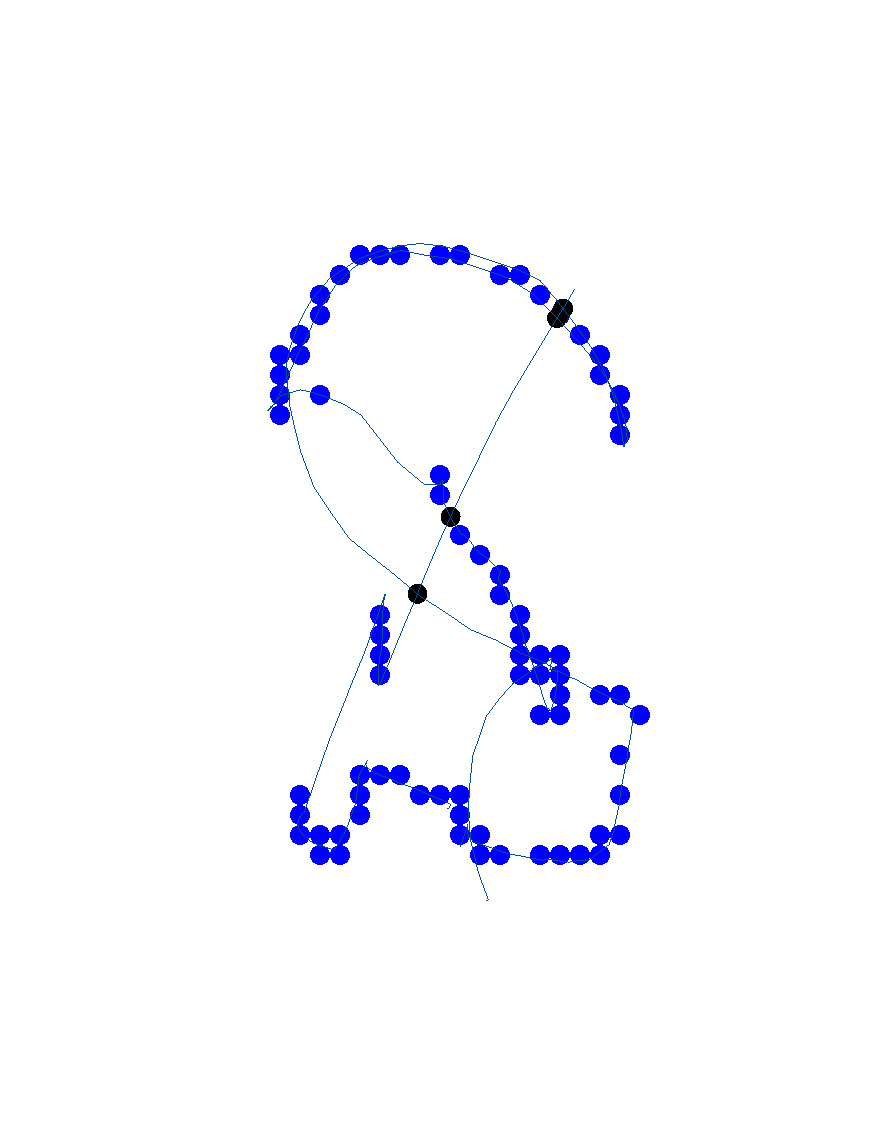

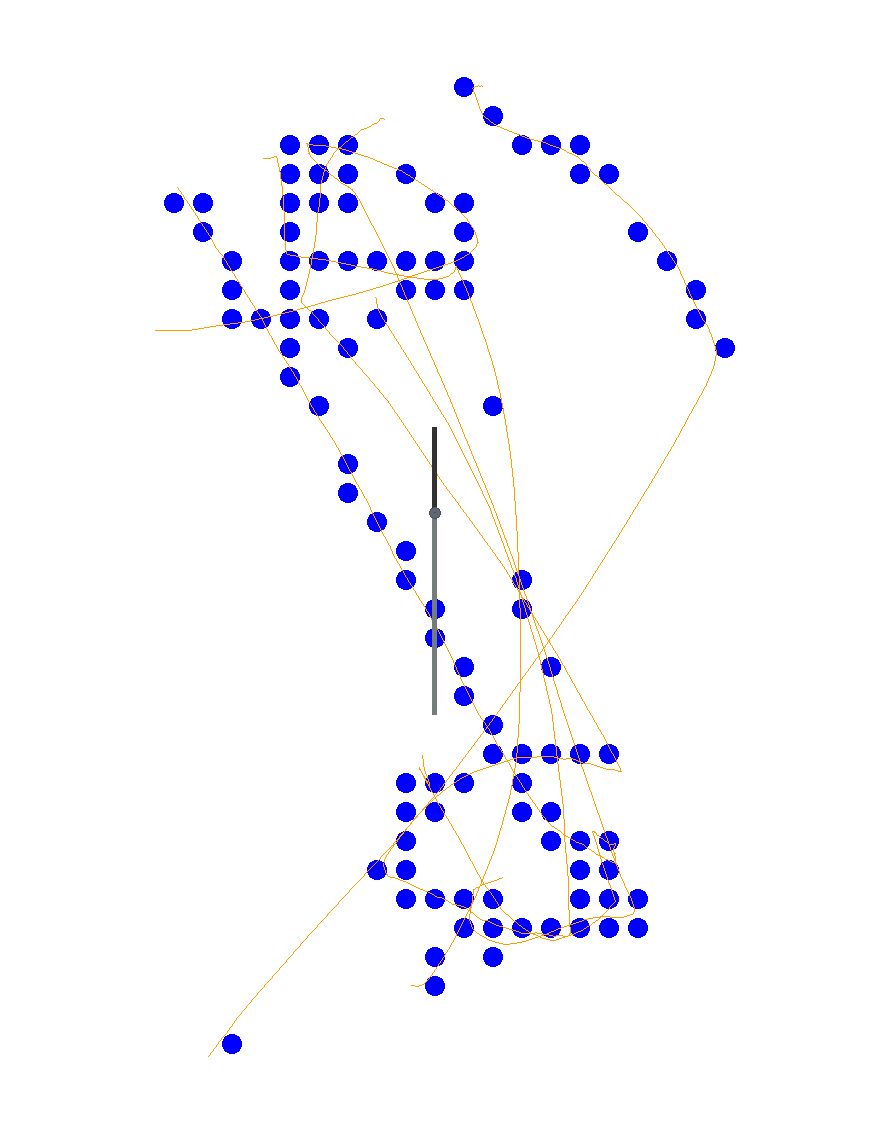

Composition #92 process. A regular green laser is moved over photographic paper, exposing it to light - drawing with light. In the next step, the paper is developed and fixed using the traditional method of photo development.

In the wake of other conceptual artists, systems artists and generative artists, like them, Schwittlick chose to refuse Romanticism and its influence, deploying strategies to avoid the human hand and all the mystique and sentimentality that pervasively come along with it. That’s why he uses code, computers, plotters and other paraphernalia. However, paradoxically, one of his most recurrent sources of entropy are his 10 years-long recorded computer mouse movements. In order to create the marks and lines of the lumonigrams, he used this specific corpus, employing a pseudo-random, or, better said, meta-random selection which isn’t done by Schwittlick himself but by his custom software system.

.jpg)

Composition #92 process. Luminograms drying while stretched on glass.

The tool, the mouse, intermediates hand and intention in the abstract realm named technically as “graphical user interface”. Motion is detected by the tool and digitised – input is being put into binary data. Digitising is a process of translating; thus, like in every translation, there is an inevitable loss of quality. This applies to all other processes where digital touch analogue. The digital is the smallest common denominator for all media and thus “flattens” everything.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Composition #92 luminogram still wet from the process of analogue photography development.

Tools are extensions of our bodies, as Marshall McLuhan concluded, and the computer mouse is no different. But the mouse line recorded by Schwittlick is a rather ambiguous body trace. If recording alters information, as we have seen, these lines are not any kind of romantic trace, like someone’s signature or a sumi-e painting. They are ambiguous and impure signs that challenge quick categorizations, they are unconscious, not controlled, not artificial and not deliberately designed. He labels these lines “passive drawing”.

.jpg)

Various sized copper apertures. Manufactured with the generous support of Jan Bernstein

The most reliable framework to approach these signs “safely”, then, is through the lenses of the algorithm’s parameters. The data is classified according to a measure of low and high entropy. “Low entropy” is a class of lines which are more predictable, therefore, formally more simple. “High entropy” has more information, thus, it entails less predictable forms. Schwittlick uses only high entropy ones in this series.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Early experiments

The database of recorded mouse movements constitute an extensive digital library of at-first-glance random scribbles. Are these drawings really random? What is randomness? John Cage said: “the first question I ask myself when something doesn't seem to be beautiful is ‘why do I think it is not beautiful?’ and very shortly you discover there's no reason. If we can conquer that dislike or begin to like what we did dislike, then the world is more open.” Can one say the drawings derived from mouse movements are random? They might appear soulless, perhaps, but are they, really?

.jpg)

.jpg)

Inspired by Siegfried Maser's Numerische Ästhetik

Schwittlick conceives these recorded movements as samples from nature, and with his context engineering thinking, refuses to create from scratch in the manner of the genius myth. Whatever comes from nature, what I call the incessant flux of events, is arguably soulful, devine, following John Cage’s steps. The inconspicuous is the degree zero of aesthetics and Schwittlick’s works are suitable media to make this evident.

Early rendering from the software development

Black, white and shades of grey resonate in the mind of the beholder: there is no message. Just like colour,

concrete photography is irreducible. The colour black leads only to itself – and also to the whole universe.

A signifier that leads to another signifier, this is Charles Sanders Peirce's semiotics, the delta of the

modern, of the search for the sign-based self-awareness of art. Schwittlick’s luminograms, like any

successful achievement in form and colour, are there to facilitate our demolishing of the common

misconception that “beauty” and “art” are subject to be defined or taken for granted as complete systems or

defined categories. Putting us to work, these images gently invite us to become more conscious of our

inherited and learnable abilities.

Text written by Lucas Rehnman, October 2023

.jpg)

Composition no. 92, Concept Line, DAM

Galerie Berlin

The series consists of 11 luminograms and 250 digital works. Below is a selection.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)